April 9 - American History Chat

Link to Video on Facebook

Link to transcript (provided by Rana Olk)

In the previous two sessions of the American history chat on March 26 and April 2 (these can be accessed by clicking on

the home button above), Heather defined the “American Paradox” (referring to the idea that equality for certain people

depends on inequality for others) and its application in the South in the 19th century. Today Heather discussed the

founding story in the American West of the rugged outdoorsman (symbolized by men such as Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett and

Kit Carson) advancing civilization and taking on ‘savages’, as opposed to the notion of the yeoman farmer in the East.

The propagation of this foundational Western myth required the development of racial hierarchies (with systematic

othering of Mexicans, Chinese and Indigenous Americans), and it took cues from how this had been done in the South. This

myth and the associated racial hierarchies were major factors that allowed the West to serve as a continual breeding

ground for oligarchy.

Links (underlined) related to topics covered in the chat

1768-1820s: Exploration and Colonial California

Quote for source: Beginning in the 16th century, California's coastal peoples began catching glimpses of an ominous and wondrous sight: strange oceangoing ships filled with bearded, pale-skinned men. After conquering and plundering the Aztec empire in present-day Mexico City in 1519, Spanish conquistadors were eagerly exploring northward, lured by rumors of fabulous golden cities. Spanish explorers found the tip of what is now Baja California in 1533 and named it "California" after a mythical island in a popular Spanish novel. Nine years later, a Spanish ship commanded by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailed as far north as present-day Oregon, making several landings along the way. During the following two centuries, Spanish galleons became frequent visitors to California's waters, sailing through on their way from Manila to Acapulco.

Ideas of Race in Early America

Quote from source: Although before colonization, neither American Indians, nor Africans, nor Europeans considered themselves unified “races,” Europeans endowed racial distinctions with legal force and philosophical and scientific legitimacy, while Natives appropriated categories of “red” and “Indian,” and slaves and freed people embraced those of “African” and “colored,” to imagine more expansive identities and mobilize more successful resistance to Euro-American societies. The origin, scope, and significance of “racial” difference were questions of considerable transatlantic debate in the age of Enlightenment and they acquired particular political importance in the newly independent United States.

The Construction of Race and Racism

This is a small pamphlet originally published by the Western States Center. Several images I have uploaded here are from this.

West of Jim Crow: A Conceptual and Empirical Framework

This is David Torres talk as part of a large on this topic entitled “Making Race in the American West.”

The Royal Proclamation of 1763

Quote from site: Britain's efforts to curtail westward expansion, most notably in the Proclamation of 1763, had little impact on the American colonists eager to settle the area west of Appalachia. This Canadian website includes the text of the Proclamation and examines the effect, if any, it had on settlement in North America.

Daniel Boone 1775 Kentucky settlement

quote from site: As eighteenth-century colonists eyed the lands across the Appalachian Mountains for further settlement, they needed explorers and promoters. Daniel Boone was both. Born in Pennsylvania in 1734, he settled his family along the Yadkin River in North Carolina in 1757. A decade later he traveled across the Appalachians to explore and hunt in the rich area around the Kentucky River. Boone and his hunting partners actually shared many values with the local Indians, but the goals of natives and newcomers diverged when permanent settlement occurred. By 1775, Boone was leading settlers through the Cumberland Gap along the Wilderness Road to the stockaded settlement of Boonesborough. He described his most significant trip, which took place between 1769 and 1771, in this selection from his 1784 “autobiography.” John Filson, a land speculator and author of Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke, created Boone’s legend as a frontier hero by appending a ghostwritten first person narrative by Boone to his promotional tract. Soon after, Boone abandoned Kentucky because of disputed land claims, and he eventually died in Missouri in 1820.

The discovery, settlement, and present state of Kentucke : and an essay towards the topography and natural history of that important country

This is a book by John Filson written in 1784, describes the discovery, purchase and settlement, and has a section on Daniel Boone.

The Border Series - Daniel Boone as a Virginian

Quote from site: Boone served with Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry in Virginia's General Assembly, having been elected in 1780 as a Delegate from Virginia's Fayette County in present Kentucky. Later he again served, that time as a Delegate from Kanawha County in present West Virginia, after having been commander of Kanawha militia. Still later, with kinfolk and friends he moved in 1799 to the Spanish territory of Missouri. There, in 1800, he was appointed Syndic ("governing officer") of the vast portion of that territory north and west of the Missouri River known as the Femme Osage district. As Syndic he was "commandant, sheriff, judge and jury." He served until 1804, after the Louisiana Purchase by the United States.

The Long Look West

Quote from site: Jefferson's original overture for a western exploratory party was directed to Revolutionary War hero, George Rogers Clark. He begins his 1783 letter to Clark with the two topics which pulled his thoughts westward: science and politics. He thanks Clark for sending him shells and seeds and assures him that he would be pleased to have as many bones, teeth and tusks of the mammoth as Clark might be able to find. Then within the same paragraph Jefferson reveals his apprehension at the rumor that money was being raised in England for exploration between the Mississippi and the Pacific, and even though it was professed as only for knowledge, he feared colonization. Jefferson then wonders, if money could be raised in this country for western exploration, "How would you like to lead such a party?" Clark declines Jefferson's request for financial reasons, but as a hero of the western theatre of the Revolution, he was quite knowledgeable of the Indians of the northwest territory and offered advice on how to best proceed among the Indian peoples, advice which Jefferson stored away for future use. In later correspondence Clark would recommend his youngest brother, William, as also knowledgeable of the Indian territory and, "well qualified almost for any business."

Discovering Lewis & Clark

This site is a virtual museum of the expedition, which began in 1803.

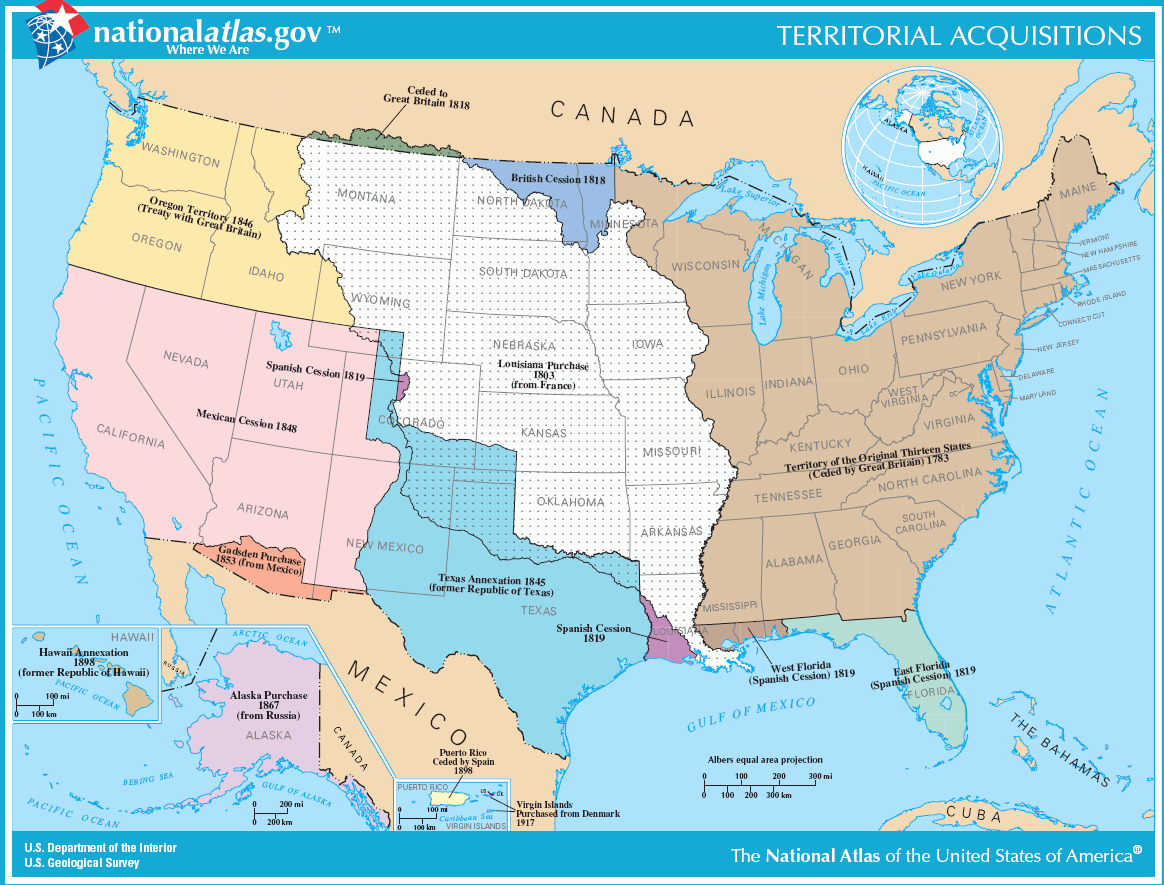

The Louisiana Purchase

Quote from site: The Louisiana Purchase (1803) was a land deal between the United States and France, in which the U.S. acquired approximately 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million.

Quote from the site: Pike expedition sets out across the American Southwest (1806)

Quote from site: Zebulon Pike, the U.S. Army officer who in 1805 led an exploring party in search of the source of the Mississippi River, sets off with a new expedition to explore the American Southwest. Pike was instructed to seek out headwaters of the Arkansas and Red rivers and to investigate Spanish settlements in New Mexico.

Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans (1815)

Quote: On January 8, 1815, the United States achieved its greatest battlefield victory of the War of 1812 at New Orleans. The Battle of New Orleans thwarted a British effort to gain control of a critical American port and elevated Major General Andrew Jackson to national fame.

Extract from Andrew Jackson's Seventh Annual Message to Congress

Quote: All preceding experiments for the improvement of the Indians have failed. It seems now to be an established fact they they can not live in contact with a civilized community and prosper. Ages of fruitless endeavors have at length brought us to a knowledge of this principle of intercommunication with them. The past we can not recall, but the future we can provide for. Independently of the treaty stipulations into which we have entered with the various tribes for the usufructuary rights they have ceded to us, no one can doubt the moral duty of the Government of the United States to protect and if possible to preserve and perpetuate the scattered remnants of this race which are left within our borders.

Vast Designs: How America came of age

This link goes to Jill Lepores's review of Howe’s book “Daniel Walker Howe’s ambitious new book, “What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848", a period in which "the United States chased its Manifest Destiny all the way to the Pacific; battled Mexico; built thousands of miles of canals, railroads, and telegraph lines; embraced universal white-male suffrage and popular democracy; forced Indians from the South and carried slavery to the West; awaited the millennium, reformed its manners, created a middle class, launched women’s rights, and founded its own literature.”

Lepore provides an interesting comparison with another book that covers the same period (“The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846" by Charles Sellers), and written around the same time as Howe's book. These books in many ways, take opposing views on the major developments in the period, and on the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Sellers explored shifts from an agrarian to an industrial market economy, and reactions to this transition, in the early 19th century most characteristically animated by the figure of Andrew Jackson, who for Sellers was a kind of hero. For Howe, John Quincy Adams is more the protagonist, and the main 19th century development he emphasizes is not the evolution of the market, but rather the communication revolution, with the growth of the postal system, the telegraph, and newspapers. More fundamentally, according to Lepore, these two authors differed on the relationship between capitalism and democracy: 'For Sellers, capitalism is the imported kudzu strangling the native pine of democracy. For Howe, capitalism is more like compost, feeding the soil where democracy grows.' Lepore lays out in some detail the point and counterpoint back and forth between Sellers and Howe. Running through this review are quotes and ideas from Thoreau's Walden, emphasizing self-reliance, frugality, and a disdain for the larger political economy. Why did Lepore do this in the review? Perhaps it was to balance the slight favor she seems to show in the review to views espoused by Howe (by usually giving him the final word in the way she laid out examples illustrating the two opposing arguments). Walden, acting as a counterpoint to Lepore's own voice, gave some of this favored status back. She does mitigate Thoreau's impact a bit at the end by noting that 'he cherished his manly self-sufficiency (even though he carried his dirty laundry to Concord for his mother to wash).'

Yet on what matters most to the content of Heather's talk today, both historians agreed, namely that: 'not everyone was better off; the people who were really “run over” in Jacksonian America were enslaved African-Americans, who toiled in the cotton fields that spread across the continent; Native Americans, who were forced from their land and marched from the South to the West, under Jackson’s brutal policy of “Indian removal”; and Mexicans, who suffered grievously during Polk’s war against Mexico in 1846-48, and even more in its aftermath.'

The Effect of Events in Europe on Mexico

This site covers a period of history lasting from 1808, when Napoleon’s brother Joseph became the de facto ruler of Spain, to the French interventions in Mexico in the late 19th century. It covers the period of Mexican independence from Spain.

Merchants of Independence: International Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1827–1860

This book covers history of trade on the Sante Fe trail. It’s introduction alone is worth reading to highlight some of major historical developments along this route.

Santa Fe Trail

This site has some nice maps of the trail, and some information about what can still be seen of it.

Kit Carson Pioneer of the West

Quote from the site: The two lives of Kit Carson have been shown all throughout American History. The life of rugged trapper and frontiersman in the new American West is one life. His second life is his larger than life figure as a legend with the likes of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett.

COMANCHE EMPIRE

Quote from site: From the 1700s-1800s the Comanches dominated the Southern Plains. Riding on recently acquired horses, the Comanche hunted, traded, and made war across a huge expanse of the Southwest. Mobility, as well as economic and militaristic supremacy, made them the first culture to sustain dominance of the frontier Texas region. The Comanche were formidable enough to block European expansion into their homeland for over 150 years, a feat no other Native American tribe achieved. The tribe called themselves Numunah, simply “Our People.” The Spanish, however, called this region Comancheria––the Comanche Empire.

Mexico’s First Black President

Quote from site: Vicente Guerrero, Mexico’s first black president, was his nation’s Lincoln. In 1829 he issued Mexico’s slavery abolition decree (which led a few years later to Texas slave holders taking Texas out of Mexico)

Santa Anna and the Texas Revolution

Quote from the site: On September 29, 1835, a detachment of the Mexican army arrived in Gonzales, Texas, a Mexican state, to confiscate a cannon . The cannon was well hidden, but eighteen armed men stood in plain sight. They taunted the Mexicans to "come and take it." The two sides talked and dickered, but no action was taken. However, the little band of men grew to 167 in two days. Early the next morning the Texans attacked the Mexican camp believing they were going to attack that day (Lord 38). With this attack the Texas Revolution was started. It was a revolution that Texas would eventually win. One of the greatest helps to the Texan cause was Santa Anna, the Mexican president, who provided the cause for revolution, stirred up the Texans' anger and zeal, and caused the Texans to win the final battle at San Jacinto.

Remember The Alamo! The Truths And Myths Surrounding The Battle

Quote from the site: The commonly-accepted version of facts and events of the Battle of the Alamo is that a handful of brave (and heavily outnumbered) English-speaking Anglo-Saxon American rebels (called Texians) defended Fort Alamo near San Antonio.They were supposedly fighting for their right to freedom and independence from the tyrannical oppression of the Mexican government (Texas was then a part of Mexico, which had itself recently achieved independence from Spain). The leader of the defense, Colonel Travis, apparently drew a line in the sand and asked for those willing to give their lives defending the fort to step forward. All but one man crossed, despite knowing that death was an inevitability. After a thirteen-day siege and a climactic two hour battle, all 189 fort defenders died in battle. Davy Crockett died with his trusty rifle, “Old Betsy” in his hands, with dozens of dead Mexicans troops at his feet. Many of the aforementioned “facts” about the battle contain grains of truth, but much of them are clear embellishments. First and foremost is the falsehood that the defenders of the Alamo were righteous revolutionaries oppressed by the tyrannical Mexican regime.[emphasis added]

How U.S. Westward Expansion Breathed New Life into Slavery

quote from the site: To understand the story of enslavement in the West is to understand the history of land acquisition, cotton production and gold fever. Leaving coastal states in search of farmable land and natural resources, settlers pushed their way west—and once they crossed the Mississippi River—into newly acquired Louisiana and later Texas. The fever of Manifest Destiny, a term coined in 1845 by American journalist John O’ Sullivan, justified territorial expansion. White settlers believed it was their duty and right to conquer the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific, to spread their democratic ideals and “civilized” ways.

Guide to the Mexican-American War on the Library of Congress website

Opposing viewpoints on the Mexican-American War

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)

quote from site: In December 1845, the U.S. Congress voted to annex the Texas Republic and soon sent troops led by General Zachary Taylor to the Rio Grande (regarded by Mexicans as their territory) to protect its border with Mexico. The inevitable clashes between Mexican troops and U.S. forces provided the rationale for a Congressional declaration of war on May 13, 1846. Hostilities continued for the next two years as General Taylor led his troops through to Monterrey, and General Stephen Kearny and his men went to New Mexico, Chihuahua, and California. But it was General Winfield Scott and his army that delivered the decisive blows as they marched from Veracruz to Puebla and finally captured Mexico City itself in August 1847. Mexican officials and Nicholas Trist, President Polk's representative, began discussions for a peace treaty that August. On February 2, 1848 the Treaty was signed in Guadalupe Hidalgo, a city north of the capital where the Mexican government had fled as U.S. troops advanced. Its provisions called for Mexico to cede 55% of its territory (present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Nevada and Utah) in exchange for fifteen million dollars in compensation for war-related damage to Mexican property.

Gold rush in California

Quote from the site: The discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill on January 24, 1848 unleashed the largest migration in United States history and drew people from a dozen countries to form a multi-ethnic society on America's fringe. The promise of wealth forever altered the life expectations of the hundreds of thousands of people who flooded California in 1849 and the decade that followed. The gold also fired up the U.S. economy and fueled wild dreams like the construction of a cross-country railroad line.

Horses and Native Americans

Quote from the site: The early relationship between Native Americans and horses was not always mutually beneficial. Some tribes, especially the Apache, acquired a taste for roasted horse meat. After 1680, the Pueblo tribes forced the Spanish out of New Mexico. Many horses were left behind. The Pueblo learned to ride well but didn't live by the horse. They mainly valued the horse as food and as an item to trade with the Plains tribes for jerked buffalo meat and robes. Horses and horsemanship gradually spread from tribe to tribe until the Native Americans of the Plains became the great mounted buffalo hunters of the American West.

Comanche Feats of Horsemanship

High resolution print featuring Comanche Horsemanship.

National Park Service’s site on the Santa Fe Trail

Quote: Deceptively empty of human presence as the prairie landscape might appear, the lands the trail passed through were the long-held homelands of many American Indian people. Here were the hunting grounds of Comanche, Kiowa, southern bands of Cheyenne and Arapaho, and Plains Apache, as well as the homelands of Osage, Kansas (Kaw), Jicarilla Apache, Ute, and Pueblo Indians. Most early encounters were peaceful negotiations centering on access to tribal lands and trade in horses, mules, and other items that Indians, Mexicans, and Americans coveted. As trail traffic increased, so did confrontations - resulting from misunderstandings and conflicting values that disrupted traditional life ways of American Indians and trail traffic. Mexican and American troops provided escorts for wagon trains. Growing numbers of trail travelers and settlers moved west, bringing the railroad with them. As lands were parceled out and the bison were hunted nearly to extinction, Indian people were pushed aside or assigned to reservations.

Reconstructing Approaches to America’s Indian Problem

Quote from the site: The decline of Native American political autonomy in the second half of the nineteenth century was one of the results of increasing national authority that also irrevocably changed the character of the American West. With its powers invigorated by the demands of war, the federal government, having abolished slavery, turned in the post-war period to address its remaining, and largely western, racial and moral problem groups: the Mormons, the Chinese, and Native Americans. Native American populations, living at various stages of what nineteenth-century Americans called civilization, proved a particularly tricky segment of the population to integrate into the American body politic. The nineteenth century’s Indian “Problem” or “Question” took many forms

HCR has mentioned the effects of the Civil War in the West. This podcast featuring Megan Kate Nelson, author of Three Cornered War, tells the story through the tales of nine historic figures, who together provide the perspectives of native Americans, Unionists, Confederates and others who moved through the West at the time.

23 Great Plains Indian Wars

Quote from site: The Plains were the last area in the Lower 48 where Indians lived independently before being forced onto reservations. When you hear people talk about Indian Wars in American history, they’re usually referring to warfare on the Plains during and after the Civil War, starting with the Dakota War of 1862 through the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. The same Union Army that fought Confederates was fighting a simultaneous war against Plains Indians, and even employed the same total war tactics used in W.T. Sherman’s March, Philip Sheridan’s (Shenandoah) Valley Campaigns, and U.S. Grant’s Siege of Vicksburg. Sherman and Sheridan both fought out west after the Civil War while Grant oversaw Indian affairs as president from 1869-1877.

The Dark Underbelly of Jefferson Davis’s Camel Core

quote from the site: Aside from his truncated term as Confederate president, Jefferson Davis might best be known for his camel experiment: the importation of some seventy-five camels for military testing in Texas and the southwest in the late 1850s. He launched the offbeat operation while serving as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, an exceptionally creative period in Davis’s life. Among other efforts, Secretary Davis ordered surveys for a transcontinental railroad, organized new cavalry regiments, and purchased the camels. The Army’s camel trials, which included surveying expeditions in Texas’s Big Bend region and along the 35th parallel to California, went well until the Civil War cut them short. By 1866, the surviving animals had been sold to circuses and mining companies or simply turned loose to fend for themselves.

Lynch Mobs Killed Latinos Across the West. The Fight to Remember These Atrocities is Just Starting

quote: Lynchings have long been associated with violence against African-Americans in the American South, and these atrocities are remembered at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama. Lynchings of Hispanics have faded into history with less attention. Often, they have been portrayed as attempts to exercise justice on behalf of white settlers protecting their livestock or claims to land. But a new movement is underway to uncover that neglected past. It has unleashed discussions about the scramble for land or mining claims that frequently influenced these lynchings, as well as the traces of such episodes in resurgent anti-Latino sentiment and the question many parts of the United States are confronting: Who gets to tell history?

Lynching a Woman in Gold Country

quote from site: The Fourth of July celebrations in Downieville were extra raucous in 1851. California had just gained statehood on Sept. 9, 1850, so the small mining town at the north fork of the Yuba River pulled out all the stops. What began with parades and a speech from the state’s first governor ended with the lynching of Josefa Segovia, the only hanging of a woman in California state history.

Lynching in America

Quote for the source: During the period between the Civil War and World War II, thousands of African Americans were lynched in the United States. Lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. These lynchings were terrorism. “Terror lynchings” peaked between 1880 and 1940 and claimed the lives of African American men, women, and children who were forced to endure the fear, humiliation, and barbarity of this widespread phenomenon unaided.

The Law that Ripped America in Two

Quote from the site: Ironically, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, passed by Congress 150 years ago this month (100 years to the week before the landmark Supreme Court decision—Brown v. Board of Education—barring school segregation), was meant to quiet the furious national argument over slavery by letting the new Western territories decide whether to accept the practice, without the intrusion of the federal government. Yet by repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had outlawed slavery everywhere in the Louisiana Purchase north of Missouri’s southern border (except for Missouri itself), the new law inflamed the emotions it was intended to calm and wrenched the country apart.

Chinese experience in 19th century America

Quote from the site: Chinese immigrants had come to San Francisco as early as 1838, but large numbers of Chinese only began to come in 1850 for the same reason many Americans were flocking to California - the 1849 Gold Rush. The Chinese immigrants were mainly peasant farmers who left home because of economic and political troubles in China. Most intended to work hard, make a lot of money, and then return to their families and villages as wealthy men. In this goal, the Chinese did not differ from many immigrants who came to the United States in the 19th century. Living together in communities and neighborhoods, they, like all immigrants, maintained their culture. However, while many Americans looked down on all immigrants, the Chinese were considered racially as well as culturally inferior. Most Americans believed that the Chinese were too different to ever assimilate successfully into American culture. This view was expressed and reinforced by the stereotypic images of Chinese immigrants recorded in the media of the time.

“An aristocracy of color”: Race and reconstruction in post -Gold Rush California

Quote from site: In the second half of the nineteenth century, California was the most racially diverse region of the United States. Home to Asians, African Americans, Native Americans, Latinos and European Americans, California was the first place Americans struggled with the task of constructing a multi-racial society of free people. Initially, Californians dealt with that diversity by ignoring it. Before the Civil War, California law recognized only a simple division between white and non-white, effectively treating all non-whites the same. Historians of California’s racial past have generally trod a similar path, writing histories of racial experience in which each non-white racial group was similarly oppressed by white racism. Yet by the end of the Reconstruction era, California law not only recognized differences between non-white racial groups, it treated each racial group differently. Amidst the turmoil of Civil War and Reconstruction, Californians developed a complicated racial hierarchy that drew distinctions between non-white racial groups even as it set whites apart from, and above, other races. This dissertation traces the process by which Californians, white and non-white, organized their society around racial difference, and examines the ideas and practices which justified their new racial scheme. The new racial hierarchy encouraged competition between non-whites for position within the scale, effectively legitimizing that scale and enlisting non-whites in support of white supremacy. By emphasizing the ways in which California’s non-white minorities cooperated with and competed against each other in their battles with white oppression, this new interpretation reveals a more muscular racial dynamic at work in the maintenance of white supremacy during the nineteenth century than previously acknowledged. This dissertation’s multi-racial, western perspective challenges traditional arguments concerning the development of white racial identity in nineteenth-century America which focus exclusively on binary relationships between black and white, free labor and slave. Finally, through its focus on law and Reconstruction, this thesis connects the histories of the South and West, and renders both regional histories central to national history

Greaser Act (1855)

quote: All persons who are commonly known as “Greasers” or the issue of Spanish and Indian blood, who may come within the provisions of the first section of this Act, and who go armed and are not known to be peaceable and quiet persons, and who can give no good account of themselves, may be disarmed by any lawful officer, and punished otherwise as provided by the foregoing section.

The slaveholding oligarchy was defeated in the Civil War. But concentrations of wealth and power continue to threaten our democracy

Quote: In From Oligarchy to Republicanism, a stimulating, if often cantankerous, history of the Civil War and Reconstruction, political scientist Forrest Nabors argues that the problem of plutocracy and the fate of the Confederacy were always deeply intertwined. Beginning in the 1830s, the United States had become not one country, but two: a northern republican regime that remained true to the vision of the founders, and a southern oligarchic regime that rejected the country’s original core values. In Nabors’s telling, the fundamental clash between North and South was not over slavery or states’ rights, but over which of these two political ideals would prevail.

The Politics of Law and Race in California, 1848-1878

Quote: In the past two decades historians have begun to reassess California's history, probing the notions of inevitability, progress, race, gender, and politics to reveal a context far more complex, dynamic, and nuanced than was once believed.5 From the beginning, racial and ethnic conflict have been embedded in the matrix of California's development. The pre-statehood invasion of an army of Anglo-American and European immigrant entrepreneurs and gold seekers overwhelmed, supplanted, and eventually delegitimated Indians, Californios, African Americans, Asians, and other people of color. The influx of white Americans gave rise to "Anglo" domination and established a society that severely marginalized California's other populations.

The “Lost Cause” Goes West

Quote: California once housed over a dozen monuments, memorials, and place-names honoring the Confederacy, far more than any other state beyond the South. The list included schools and trees named for Robert E. Lee, mountaintops and highways for Jefferson Davis, and large memorials to Confederate soldiers in Hollywood and Orange County. Many of the monuments have been removed or renamed in the recent national reckoning with Confederate iconography. But for much of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, they stood as totems to the “Lost Cause” in the American West. Despite a vast literature on the origins, evolution, and enduring influence of the Lost Cause myth, little is known about how this ideology impacted the political culture and physical space of the American West. This article explores the commemorative landscape of California to explain why a free state, far beyond the major military theaters of the Civil War, gave rise to such a vibrant Confederate culture in the twentieth century. California chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) carried out much of this commemorative work. They emerged in California shortly after the organization's founding in Tennessee in 1894 and, over the course of a century, emblazoned the Western map with salutes to a slaveholding rebellion. In the process, the UDC and other Confederate organizations triggered a continental struggle over Civil War memory that continues to this day.

The Bascom Affair

Quote: The Bascom Affair is considered to be the key event in triggering the 1860s Apache War. The Apache Wars were fought during the nineteenth century between the U.S. military and many tribes in what is now the southwestern United States. The triggering incident took place in 1861 in the area known as Arizona and New Mexico.

The Dakota War (1862)

quote: For six weeks in 1862, war raged throughout southwestern Minnesota. The war and its aftermath changed the course of the state’s history. Some of the descendants of those touched by the war continue to live with the trauma it caused.

Mass Execution of Dakota Indians

On Dec. 26, 1862, 38 Dakota Indians were executed by the U.S. government during the U.S. Dakota War of 1862

The “Lieber Code” – the First Modern Codification of the Laws of War

Quote: On April 24, 1863, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln issued “General Orders No. 100: Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field,” commonly known as the “Lieber Code” after its main author Francis (Franz) Lieber. The Lieber Code set out rules of conduct during hostilities for Union soldiers throughout the U.S. Civil War. Even today, it remains the basis of most regulations of the laws of war for the United States and is referred to in the foreword to the Department of Defense Laws of War Manual. The Lieber Code inspired other countries to adopt similar rules for their military and was used as a template for international efforts in the late 19th century to codify the laws and customs of war.

Navaho Long Walk (1864)

Quote: Major General James H. Carleton ordered Christopher (Kit) Carson to defeat the Navajo resistance by conducting across the Navajo homelands. Carson burned villages, slaughtered, and destroyed water sources in order to reduce the Navajo to starvation and desperation. With few choices, thousands of Navajo surrendered and were forced to march between 250 and 450 miles to the Bosque Redondo Reservation.

Sand Creek Massacare (1864)

Quote: There were many such atrocities in the American West. But the slaughter at Sand Creek stands out because of the impact it had at the time and the way it has been remembered. Or rather, lost and then rediscovered. Sand Creek was the My Lai of its day, a war crime exposed by soldiers and condemned by the U.S. government. It fueled decades of war on the Great Plains. And yet, over time, the massacre receded from white memory, to the point where even locals were unaware of what had happened in their own backyard.

The Reconstruction Republicans: Answering the Slaveocratic Revolution

Quote: Political oligarchy grounded on slavery is the primary cause of that second-class citizenship. Racism was one of its consequences, one particular instrument among others by which that oligarchy maintained its control.